Fifty participants from a variety of medical backgrounds across the region took part in Lancashire Teaching Hospital’s largest MAJAX Simulation days at Chorley Hospital, which recreated the aftermath of a major trauma incident.

The participants were made up of final year Emergency Medicine registrars, Emergency Medicine Nurses, Surgeons, Orthopods, Anaesthetists, ODPs and Anaesthetic Nurses.

The event was organised was Mark Brown, Senior Clinical Fellow of LTH’s Emergency Department, and Kristen Walthall, Clinical Director for Simulation and Human Factors and a Consultant in Emergency Medicine and Simulation, with the day’s operation being supported by the Trust’s Resus and Simulation Team, led by Sarah Causey-Freeman.

The organisers and their support teams worked tirelessly over the course of two days to recreate a simulated hospital environment at the LIFE Centre in Chorley, with areas varying from P1-P3, Resus, Major or Minor, which were supported by wider departments, including actual Radiologists to support in X-Ray and CT, along with hypothetical treatment areas such as theatre and ICU, to give participants a unique experience.

Kirsten states. “This is the first Major Incident Simulation that has been done on this scale in the region, perhaps even the Northwest… This is as close as we can get to the real thing, although it’s still a very limited experience of this sort of event.’

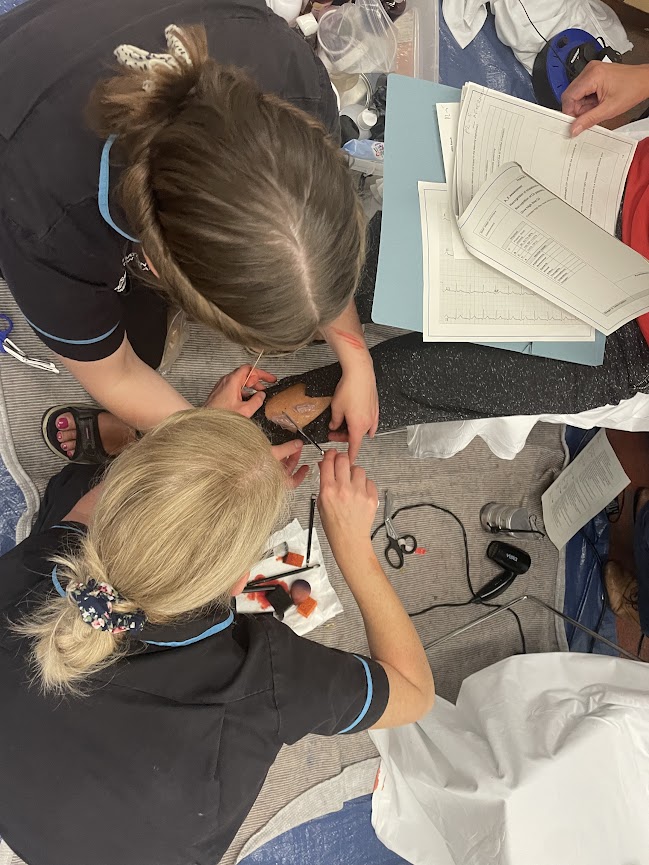

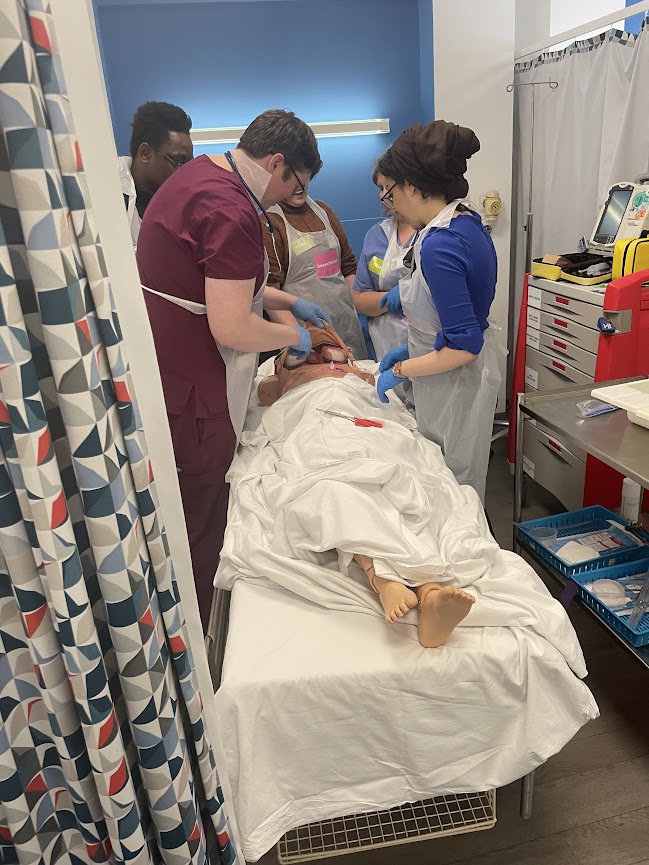

In addition to the facilities, the event featured a plethora of immersive effects and equipment, including the use of interactive mannequins and the use of moulage makeup, to replicate realistic injuries. Live actors were also used in the simulation to increase the immersion.

The group, made up of varying age and backgrounds, portrayed victims of the explosion, one actor was even accompanied by her young baby, providing the participants with a unique paediatric experience.

The actors, many of whom were from medical backgrounds themselves, displayed symptoms of varying complexities, the cause of which the participants had to discern and treat.

The event is also the first time that the Simulation Team has applied moulage onto real actors and Sarah states that is the ‘beauty’ of experiences such as this. She says.

‘It allows the participants to visualise the injury rather than just imagine it. That is the joy of simulation. (The event) is a no-lose situation. If they treat the patient properly, great. If they miss the diagnosis, then they learn.’

To make the event as useful as possible to those in attendance, Mark adds that they altered trust protocol to enhance the learning parameters.

‘(We used) the generic principles of major incident rather than the trust major incident protocol because the wider staff are regional. This allows the rotational staff to apply what we teach to their local protocols.’The day began with participants being briefed with minimal information, like they would receive in an actual major trauma incident.

Informed only that there had been a gas leak and a subsequent explosion on a housing estate, the medical team were informed they had to deal with the aftermath.

Before any new patients could even arrive, the participants had to assess their existing patients, discerning who was to be moved out in preparation of the major incident victims, whilst being informed they are to expect ten Resus patients and up to thirty Minors victims, statistics that proved to be untrue.

Sarah says that simulation events are vital.

‘(Major trauma) events like this may happen throughout your career. Major car pileups, terror incidents, explosions… but they do not happen frequently, and it can be a case that many medical staff do not see them at all during their training.’

Kristen adds. ‘We’re giving them a practice run. It forces them to think on their feet. The treatment requires organisation of limited staff and resources, makes them prioritise patients. For example, there is only one Ortho doctor. Who are they going to treat? They are space issues. Who gets a bed and where?’

Split into two, one and a half hour sessions, the participants took turns working across the three teams, with varying expectations, often working against the clock. In Resus, the most severe patients had to be treated within ten minutes. Majors, required treatment within thirty minutes and finally, Minors, where the patients could not be sent home until they had been seen.

Together, were responsible for all areas of patient care, from triage all the way through to discharge or referral, for all who walk, or are pushed through, the doors. Including, who they decided to treat first.

Whilst some injuries were straight forward, including shards of glass stuck in skin and abrasions, others were not. Some symptoms were ‘red herrings’, with complex scenarios placed into the simulation, with certain actors being briefed that their ailments must worsen and adapt, requiring the participants to think on their feet and adapt their care.

One such patient was Scott, who, after initially presented with smoke inhalation and little more than a sore throat and a croaky voice. However, his condition quickly worsened into a ‘Stridor’ injury, otherwise known as an airway obstruction. He subsequently which resulted in a complex care tracheostomy, the procedure of which was performed on a mannequin.

Other situations were even more severe, with participants having to overcome certain human factors obstacles, including patients losing consciousness and growing unable to advocate for themselves and their symptoms, with others ultimately passing away despite intervention.

Sarah describes the situations as necessary ‘moral choices’, certain patients presenting with ‘no intervention injuries’, with the goal of treatment for them to be pronounced dead. She says, ‘when dealing with patients on such a mass scale you have to perform viability tests. Can they be treated or is this time being wasted, taken from another patient?’

As each scenario reached its end, the performance of each team was then ‘debriefed’ by the overseeing staff who informed them of the correct process of care. Together, they then explored which method of treatment the participants took and why, whilst also looking at what could possibly be done differently.

During one such debrief, Kristen advised participants. ‘Trust your role. You have to keep control and remain in control. You have to keep moving because if you don’t there is a breakdown in the flow of treatment.’

During one such debrief, Kristen advised participants. ‘Trust your role. You have to keep control and remain in control. You have to keep moving because if you don’t there is a breakdown in the flow of treatment.’

After an overwhelming day, the participants were eventually given the all clear, being informed that the ‘Major Incident Team can stand down.’ After which they received a full debrief of not only the day’s events, but also a mental health check, with all those who had taken part in the day’s event.

During this, staff and participants unanimously agreed that all forms of communication were ‘absolutely vital, with each other, with patients and across teams. ’The day was regarded a success by all in attendance. With Mark describing the event as ‘going much smoother than expected (for a pilot event).’

He added that the feedback from participants has also proven to be ‘overwhelmingly positive’ and that the team hope that the success of this simulation will result in many more.

‘Depending how the course evolves I see expansions to make it work better with more staff, which we hope to get the funding for. We’re pencilled in for a two-day course next year, which I think would be the optimum way of running it.’